Amway Deploys Innovation without Limits

In the world of consumer goods, Amway is a rare success story. The 56-year-old organization manufactures and distributes health, beauty and home products under brand names including Nutrilite, Artistry and eSpring in more than 100 countries and territories across Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe and the Americas. The Michigan-based company’s direct-selling model, in which distributors call Amway business owners (ABOs) market and leverage to sell products to customers, has been nothing but successful. Sales have increased 13 out of the past 15 years, despite a recession, as the organization successfully expanded its business model across the globe, capturing market share in rapidly growing Asian markets. In 2013, sales increased 44 percent from just five years earlier, hitting the $11.8 billion mark and making Amway the No. 1 direct-selling business in the world.

Business for Amway was good. However, this didn’t come about by chance.

Room for Growth

Around 2006 it was recognized that growth through regional expansion would ultimately tail off as Amway ran out of new markets to enter. In addition, a retrospective five-year analysis of its innovation pipeline revealed that the company was primarily producing incremental innovation.

To continue to grow at its current rate, the organization expanded its focus to increase its share of the markets where it already operated. In 2007, the global leadership team launched its Growth Through Innovation (GTI) initiative, which increased focus on developing and acquiring new products.

“In addition to product innovation, the R&D function was encouraged to think about innovation in broad terms and reevaluate how it conducts market research, the processes that guide product design, and how products are packaged. Business model innovation was also part of the initiative, with Amway looking at new ways to market and distribute products and services,” says Ron Sharpe, fellow — Open Innovation, Amway.

Overcoming Limitations

When it came to innovation, the prevailing attitude was that Amway could and should develop everything internally because the organization would have full control over any intellectual property. There was little oversight, and few projects were ever discontinued. Often, individual researchers made decisions about which projects to pursue.

“A lot of what was going on was long-term experienced scientists saying, ‘Hey, I think this is cool, I’m going to go work on that’. Over time, we recognized that this was a suboptimal way to meet our innovation needs,” says Sharpe.

The organization simply didn’t have the resources to devote to internal product development as some of its competitors. So the challenge became how do you achieve exponential innovation without adding corresponding exponential technical resources?

Thus, a grass roots open innovation initiative was born within Amway’s R&D function. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to overcome the company’s growth limitations. Amway could make up for its disparity in resources by partnering with third parties to develop and market their technologies. Reaching out to a broader network would allow the organization to level the playing field and innovate at the same rate as its larger competitors.

“And with more flexibility and less aggressive timelines, the Open Innovation team could focus on longer-term projects with the potential to provide more value than the incremental innovation on which we had previously focused,” says Sharpe.

But, many people across the organization did not understand why the existing processes needed to change, given that Amway was producing new products and continuing to grow. Up to the task, the a newly-formed Open Innovation team developed a compelling business case that won senior leadership’s support, as well as that of managers and scientists within the product development function.

The Road to Discovery

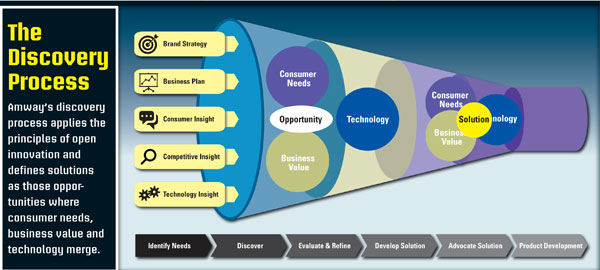

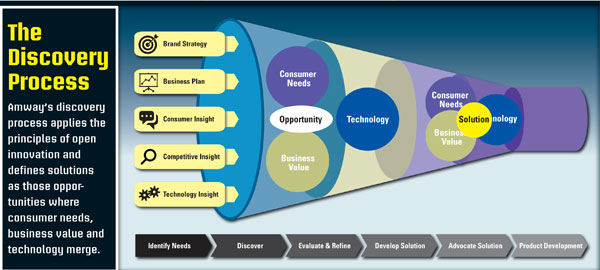

Once formally established, the Open Innovation team formalized the innovation process and established stricter business rules to guide projects. Whereas the lab was once its world, the world had now become Amway’s lab. New ideas are now identified during an annual technology planning process designed to detect new or unfilled consumer needs and needs within the businesses.

“The technology planning process allows us to look at all of our potential projects and filter them down to the handful most likely to add value to the bottom line,” says Sharpe.

For the organization to pursue an idea, it must not only be feasible but also have a clear market and align with the long-term goals of the organization. In its innovation process, Amway strives to bring together a known consumer need, a viable technology and an opportunity to create value for the business. If any element is missing, then the project is either recycled for additional incubation or put on hold until circumstances change. For example, if there is a clear customer need and potential for business value but the technology is not ready to be manufactured and marketed, then the project is put in stasis until the technology is more viable.

“We view the internal selling of every technology as a political campaign where the technology must be elected,” says Sharpe. “After a project is given a green light, we still must maintain approval ratings.”

Even with upper management’s support, Amway faced cultural barriers in rolling out and executing processes with product development and marketing. Some of the more common forms of resistance have even earned pet names, like:

The Pocket Veto: When the Open Innovation team identifies a promising technology but cannot get the marketing and product development functions to respond concerning whether they’re interested one way or another.

Deep Pockets, Short Arms: Situations where product development and marketing express a need and are interested in a particular technology but do not want to fund its development.

If You Go External, There Will Be No Internal Work: Refers to the fear that jobs will be at risk if the organization sources technology externally.

Although the Open Innovation team has not completely overcome these barriers, it has been able to mitigate many of them. For example, the technology planning process has forced product development, marketing, and other internal stakeholders to lay out their needs in a straightforward manner. In addition, employees have realized that bringing in external technologies actually creates more internal product development work because the organization must grapple with unknown technologies and shape them to its needs.

Once an opportunity is deemed worthy of pursuit, R&D leadership selects the best approach for each. If the group has the right resources and capabilities to develop a particular technology, then it may assign that project to internal development. However, if the organization does not have the right skill set or decides it does not want to invest in a given area, then the Open Innovation group may conduct external technology mining to find an appropriate third-party partner.

“This is the heart of our open innovation approach,” says Sharpe. “Once started, all projects are subject to the same checkpoints and evaluation criteria, regardless of whether they are developed internally or externally.”

A Great Business

To date, more than $500 million in products containing technology have been identified through open innovation. Without revealing specifics, Sharpe reports that the initiative has enabled Amway to introduce “hits” in both adjacent spaces and new categories.

“Amway’s Open Innovation team has built an ecosystem with the right people, processes and key strategies that allow them to capture emerging technologies and support the stage-gate product development process. Now, with the right partners in place, Amway has learned to stop worrying and embrace open innovation, creating value for their partners and creating value for Amway,” says Cheryl Perkins, founder of Innovationedge.

As Amway’s open innovation efforts grow in maturity, the company is adding more dedicated resources outside of R&D (procurement, regulatory, etc.) and placing more resources and sensing stations around the globe. Amway is also deliberately seeding its networks by maintaining relations with small to-midsized companies that may have interesting technology, but may not be technically ready, or a good market fit for one reason or another. Amway continually offers these companies advice on how to make their products and/or technology better. In return, the businesses are more likely to innovate in a direction that has more meaning for Amway.

“We will work to marry product innovation more closely with business model innovation in the future,” says Sharpe.

Now armed with structured, yet flexible product development processes and a growing network of external partners, Amway is well on its way to turning a good business into a great business, loaded with future opportunities for growth through open innovation.

More Barrier Pet Names

Business for Amway was good. However, this didn’t come about by chance.

Room for Growth

Around 2006 it was recognized that growth through regional expansion would ultimately tail off as Amway ran out of new markets to enter. In addition, a retrospective five-year analysis of its innovation pipeline revealed that the company was primarily producing incremental innovation.

To continue to grow at its current rate, the organization expanded its focus to increase its share of the markets where it already operated. In 2007, the global leadership team launched its Growth Through Innovation (GTI) initiative, which increased focus on developing and acquiring new products.

“In addition to product innovation, the R&D function was encouraged to think about innovation in broad terms and reevaluate how it conducts market research, the processes that guide product design, and how products are packaged. Business model innovation was also part of the initiative, with Amway looking at new ways to market and distribute products and services,” says Ron Sharpe, fellow — Open Innovation, Amway.

Overcoming Limitations

When it came to innovation, the prevailing attitude was that Amway could and should develop everything internally because the organization would have full control over any intellectual property. There was little oversight, and few projects were ever discontinued. Often, individual researchers made decisions about which projects to pursue.

“A lot of what was going on was long-term experienced scientists saying, ‘Hey, I think this is cool, I’m going to go work on that’. Over time, we recognized that this was a suboptimal way to meet our innovation needs,” says Sharpe.

The organization simply didn’t have the resources to devote to internal product development as some of its competitors. So the challenge became how do you achieve exponential innovation without adding corresponding exponential technical resources?

Thus, a grass roots open innovation initiative was born within Amway’s R&D function. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to overcome the company’s growth limitations. Amway could make up for its disparity in resources by partnering with third parties to develop and market their technologies. Reaching out to a broader network would allow the organization to level the playing field and innovate at the same rate as its larger competitors.

“And with more flexibility and less aggressive timelines, the Open Innovation team could focus on longer-term projects with the potential to provide more value than the incremental innovation on which we had previously focused,” says Sharpe.

But, many people across the organization did not understand why the existing processes needed to change, given that Amway was producing new products and continuing to grow. Up to the task, the a newly-formed Open Innovation team developed a compelling business case that won senior leadership’s support, as well as that of managers and scientists within the product development function.

The Road to Discovery

Once formally established, the Open Innovation team formalized the innovation process and established stricter business rules to guide projects. Whereas the lab was once its world, the world had now become Amway’s lab. New ideas are now identified during an annual technology planning process designed to detect new or unfilled consumer needs and needs within the businesses.

“The technology planning process allows us to look at all of our potential projects and filter them down to the handful most likely to add value to the bottom line,” says Sharpe.

For the organization to pursue an idea, it must not only be feasible but also have a clear market and align with the long-term goals of the organization. In its innovation process, Amway strives to bring together a known consumer need, a viable technology and an opportunity to create value for the business. If any element is missing, then the project is either recycled for additional incubation or put on hold until circumstances change. For example, if there is a clear customer need and potential for business value but the technology is not ready to be manufactured and marketed, then the project is put in stasis until the technology is more viable.

“We view the internal selling of every technology as a political campaign where the technology must be elected,” says Sharpe. “After a project is given a green light, we still must maintain approval ratings.”

Even with upper management’s support, Amway faced cultural barriers in rolling out and executing processes with product development and marketing. Some of the more common forms of resistance have even earned pet names, like:

The Pocket Veto: When the Open Innovation team identifies a promising technology but cannot get the marketing and product development functions to respond concerning whether they’re interested one way or another.

Deep Pockets, Short Arms: Situations where product development and marketing express a need and are interested in a particular technology but do not want to fund its development.

If You Go External, There Will Be No Internal Work: Refers to the fear that jobs will be at risk if the organization sources technology externally.

Although the Open Innovation team has not completely overcome these barriers, it has been able to mitigate many of them. For example, the technology planning process has forced product development, marketing, and other internal stakeholders to lay out their needs in a straightforward manner. In addition, employees have realized that bringing in external technologies actually creates more internal product development work because the organization must grapple with unknown technologies and shape them to its needs.

Once an opportunity is deemed worthy of pursuit, R&D leadership selects the best approach for each. If the group has the right resources and capabilities to develop a particular technology, then it may assign that project to internal development. However, if the organization does not have the right skill set or decides it does not want to invest in a given area, then the Open Innovation group may conduct external technology mining to find an appropriate third-party partner.

“This is the heart of our open innovation approach,” says Sharpe. “Once started, all projects are subject to the same checkpoints and evaluation criteria, regardless of whether they are developed internally or externally.”

A Great Business

To date, more than $500 million in products containing technology have been identified through open innovation. Without revealing specifics, Sharpe reports that the initiative has enabled Amway to introduce “hits” in both adjacent spaces and new categories.

“Amway’s Open Innovation team has built an ecosystem with the right people, processes and key strategies that allow them to capture emerging technologies and support the stage-gate product development process. Now, with the right partners in place, Amway has learned to stop worrying and embrace open innovation, creating value for their partners and creating value for Amway,” says Cheryl Perkins, founder of Innovationedge.

As Amway’s open innovation efforts grow in maturity, the company is adding more dedicated resources outside of R&D (procurement, regulatory, etc.) and placing more resources and sensing stations around the globe. Amway is also deliberately seeding its networks by maintaining relations with small to-midsized companies that may have interesting technology, but may not be technically ready, or a good market fit for one reason or another. Amway continually offers these companies advice on how to make their products and/or technology better. In return, the businesses are more likely to innovate in a direction that has more meaning for Amway.

“We will work to marry product innovation more closely with business model innovation in the future,” says Sharpe.

Now armed with structured, yet flexible product development processes and a growing network of external partners, Amway is well on its way to turning a good business into a great business, loaded with future opportunities for growth through open innovation.

More Barrier Pet Names

- My Needs are Secret: When there’s difficulty articulating needs and tech needs (for the Open Innovation team to find).

- Speed Waiting: When teams can’t make up their minds about whether there is interest or not.

- We’re Different, if it’s Not Created Here it Won’t Work in our Business: The assumption that internally developed technologies are inherently better.